From doing research into solar applications I have come to the personal conclusion that solar energy is misapplied in many instances. Our sun is an awesome source of energy, but all too often we use it to create electricity we store to make heat or light later. While this has some really useful applications, […]

Month: July 2011

How to Cast Lead Bullets

First of all, let me just say, I am no expert at casting lead bullets and this article is only a basic guide to get started and to show you that this is do-able for the lay person. Please visit forums like cast boolits and read manuals like Lee’s Modern Reloading, and the Lyman […]

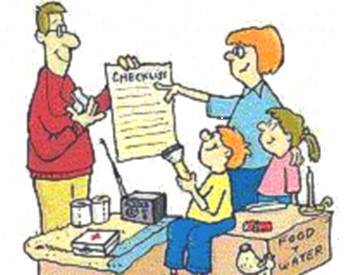

Emergency Management Principles for Prepping

Just like everybody else, I am unique. In the disaster prepper field I am unique in that I am both a diehard personal prepper and a college trained emergency management professional. I did not become one because of the other; my personal preparedness mindset comes from my parents, as well as my internal system of […]